Photography Courtesy of LaFrancine Burton

“I remember when … I would sit at my mother’s feet, and she spoke of a time … when there was an entire black community where the RP Funding Center now stands.”

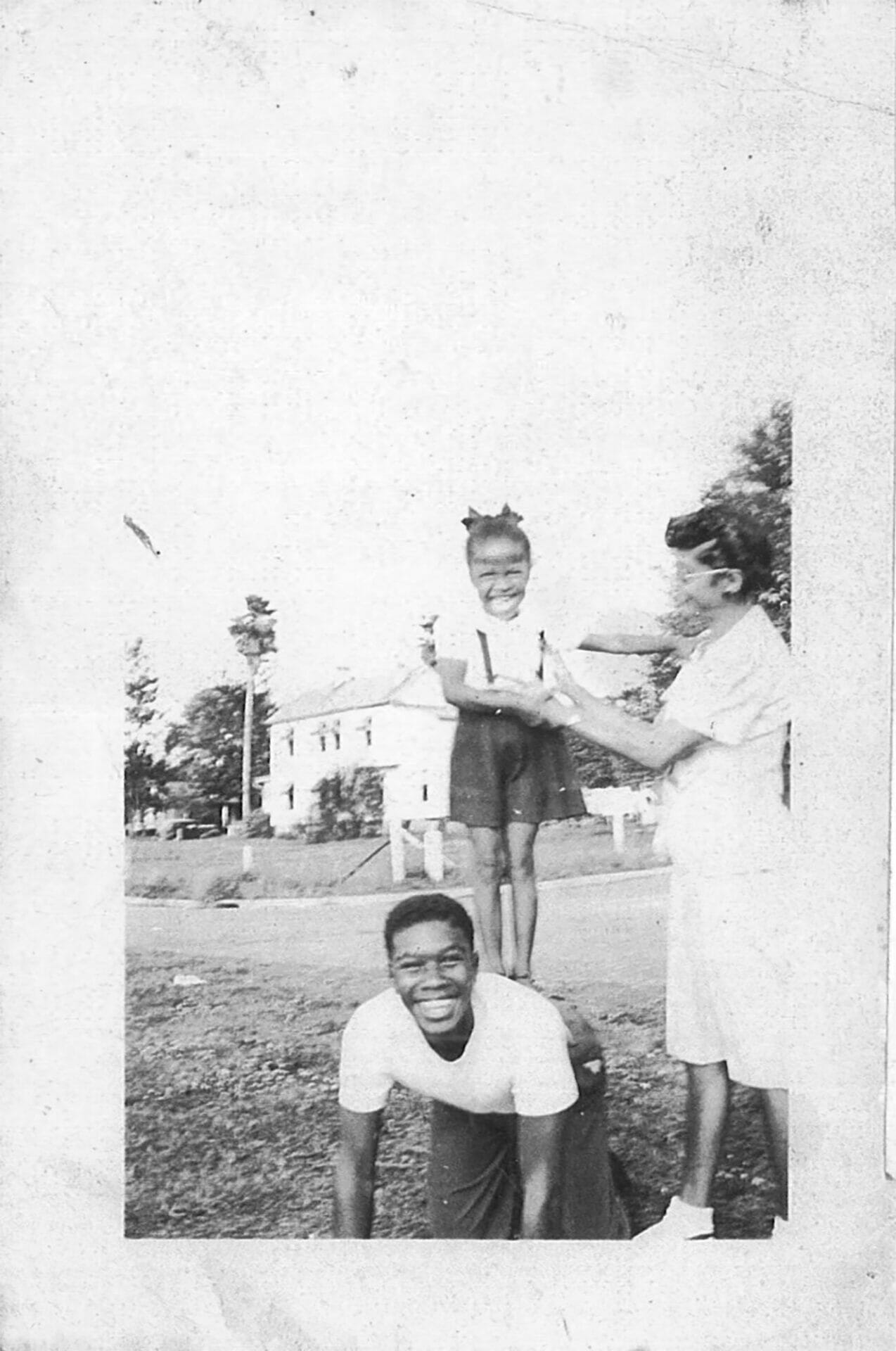

During the days of segregation in the 1800s, prominent black communities existed in Lakeland. The tales of communities like Moorehead and Teaspoon Hill were long untold until Lakeland historian LaFrancine Burton decided to document their rich histories.

In 2001, Burton became known as the foremost narrator of Lakeland’s black history. Beginning that year and through 2007, Mrs. Burton wrote a total of 33 articles that appeared in The Ledger telling the story of Lakeland’s black history and adding much-needed context to an already rich city history.

In 2001, Burton became known as the foremost narrator of Lakeland’s black history. Beginning that year and through 2007, Mrs. Burton wrote a total of 33 articles that appeared in The Ledger telling the story of Lakeland’s black history and adding much-needed context to an already rich city history.

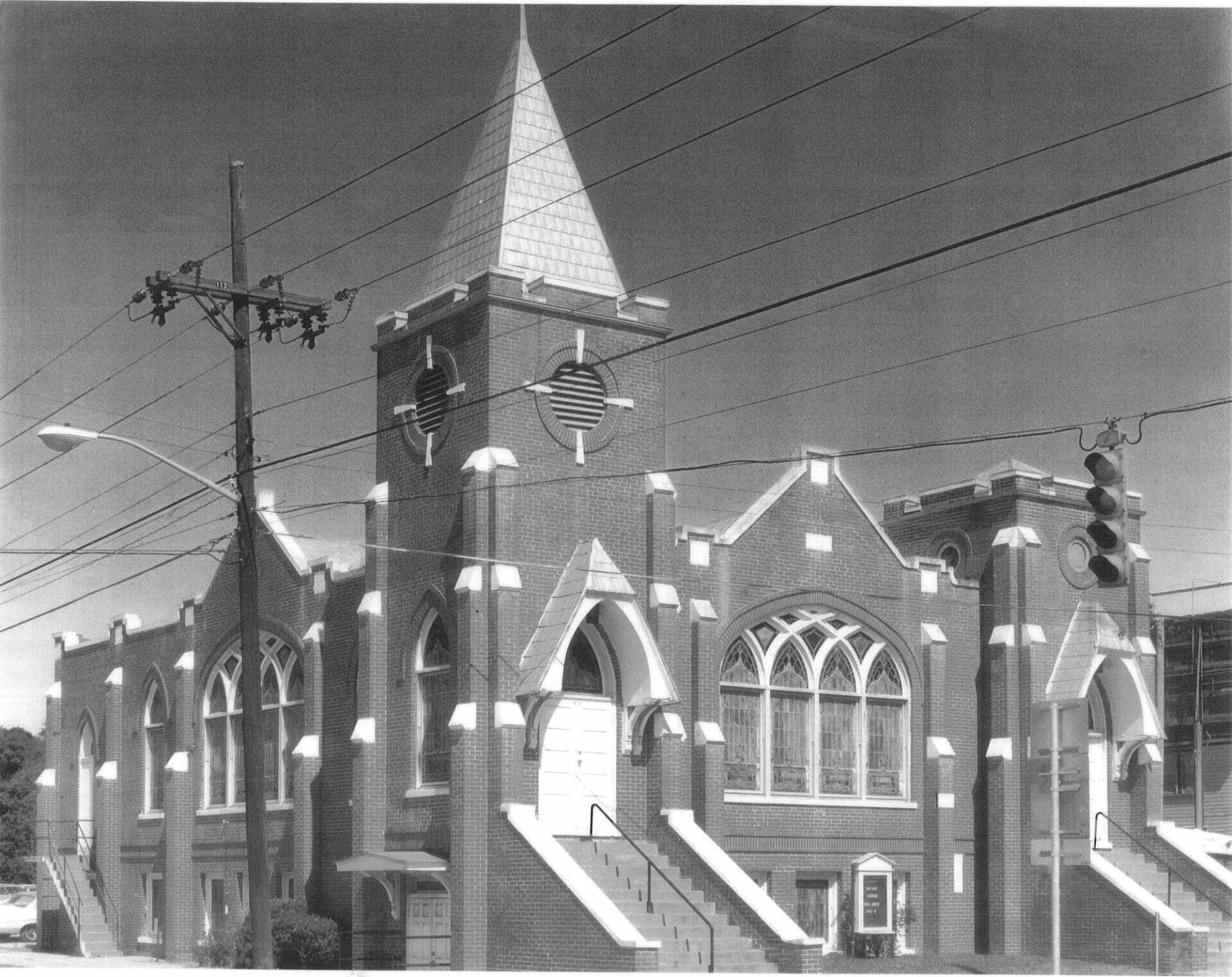

Because of Burton’s diligent research, we know that Moorehead was filled with schools, churches, and places of commerce. It was a calling card for our county, for black people both young and old who were encouraged by prominent figures, like Booker T. Washington, to move here. Moorehead was filled with pioneers like Dr. David J. Simpson, Lakeland’s first black doctor.

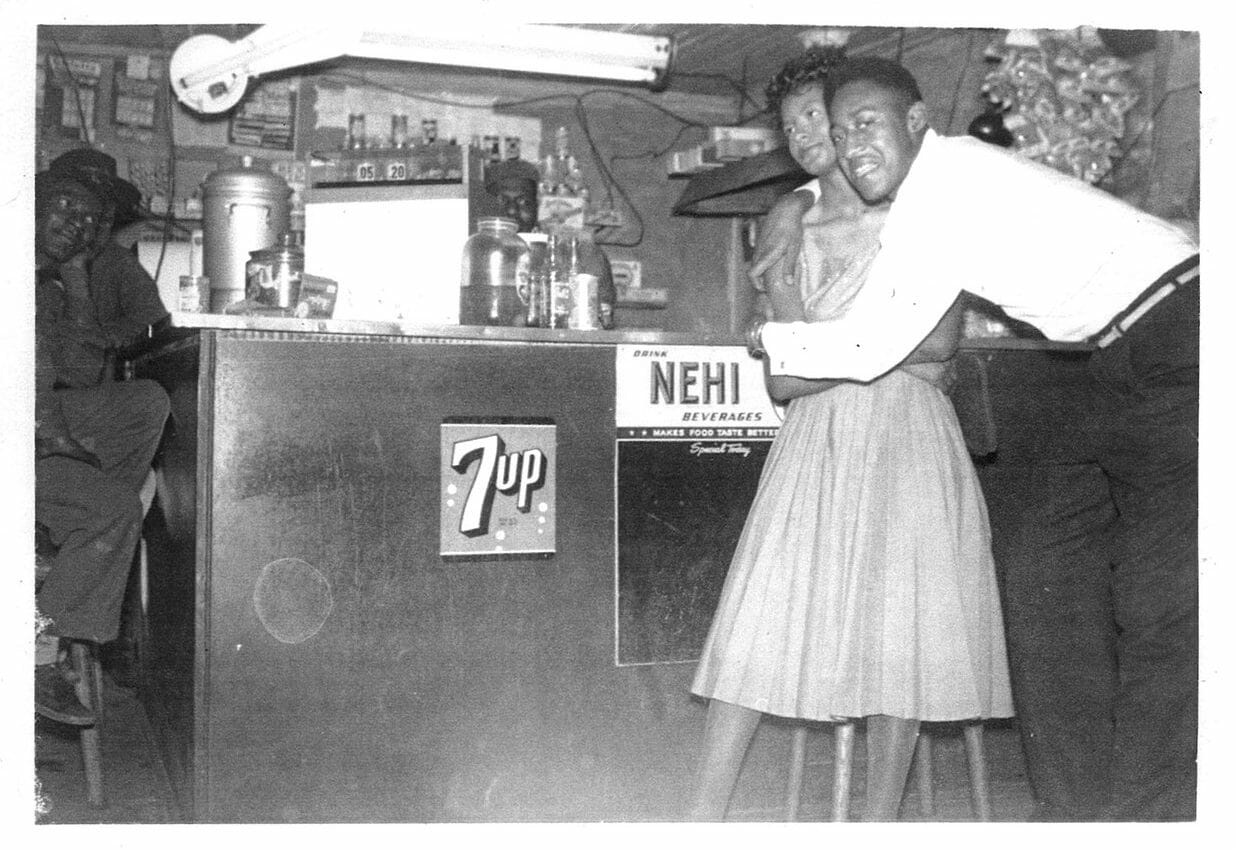

Teaspoon Hill was a mecca of black-owned businesses — many of which stood for years even after desegregation. Black businesses lined the streets of North Florida Avenue, North Street (now Memorial Boulevard), and North Dakota Avenue (now Martin Luther King Boulevard). Those communities and the families within them possessed deep pride over their accomplishments, and Burton believed that they deserved to be credited in our city narrative.

The city of Lakeland bought and demolished structures in Moorehead: 131 mostly modest houses, some black-owned businesses, and four churches, located west of downtown.

Burton is a Lakeland native, born on the same property her grandfather bought 100 years ago. She attended all-black schools — Moorehead Elementary and Rochelle Jr./Sr. High — and she, along with Delores Belle, became the first two black students to graduate Lakeland Senior High School.

She described the transition from all-black schools to Lakeland Senior as a tumultuous one. “I had always heard about the idea ‘separate but equal.’ It was the biggest lie in the world. It was not equal. When I was at Rochelle, we were lucky if we got a new book … But every book was new at Lakeland High School. The desks were new, and there was air conditioning; it was totally different. The lunchroom was even different. I had never had pizza in my life. I didn’t know they served pizza in the lunchroom. It was totally different. It was absolutely a culture shock.”

The transition gave Burton the confidence to talk to people, all kinds of people. She credits a key inspiration to her, Maya Angelou. “[Angelou] is my favorite author. She had to grow out of her shell. She found so many experiences outside of the bubble that she was raised in: learning different cultures, meeting different people, and traveling to different places. I look at her, and I can relate. I love meeting people, and I love hearing about other folks’ lives.”

[pull quote] “When I was at Rochelle, we were lucky if we got a new book … But every book was new at Lakeland High School.”

Burton was inspired to use her gifts to research her own black history after hearing Cantor Brown’s speech for Black History Month in Bartow. She went to the library and asked about black history, and they said, “There’s nothing here.”

Burton recalls Dr. [David] Logan telling her, “We don’t have anything here, but whatever you can find, if you bring it and share it with us, we will place it in a special collection.”

Stella Butler and R.L. Keith at Shanghai’s Juke Joint owned by Burton’s father.

With that, Burton started visiting the homes of folks who used to live in Moorehead before it was torn down. They began to share their stories with her; she took pictures of them and wrote down the city’s history from their perspective. The articles grew in popularity, and soon people called on Burton to write all kinds of stories telling about the rich history of Moorehead and its residents’ integral shaping of our community.

As an amateur researcher, Burton has received numerous awards and recognitions for having researched and documented some of our local black history. “I was very proud to receive the historic marker in recognition of all the black folks who had lived there, had their communities there, their churches there, the schools there … That was a fight, but I loved it! And finally getting Polk County’s black history documented was a huge win.”

[pull quote] In the future, Burton wants to continue to see black people sharing their stories with their cities.

When Burton reflects on historic moments that mean the most to her, she recognizes the Civil Rights Era that occurred while she was at Lakeland Senior. Every evening, she says, her family would watch Chet Huntley and David Brinkley on the evening news, and she would see her grandfather cry. “I can remember that vividly, and I guess that will always stay with me. That fight, and hearing him talk about what he had to go through as a black man … When I hear folks say nothing has changed, that is a lie. A lot has changed.”

When Burton reflects on historic moments that mean the most to her, she recognizes the Civil Rights Era that occurred while she was at Lakeland Senior. Every evening, she says, her family would watch Chet Huntley and David Brinkley on the evening news, and she would see her grandfather cry. “I can remember that vividly, and I guess that will always stay with me. That fight, and hearing him talk about what he had to go through as a black man … When I hear folks say nothing has changed, that is a lie. A lot has changed.”

Burton’s work saw a high point on February 23, 2002, when the City of Lakeland placed a historical marker on the site in the roundabout entrance off Lime Street, which still stands to this day.

In the future, Burton wants to continue to see black people sharing their stories with their cities. She expects to see the black community represented in downtown Lakeland at City Hall. “I want to see younger black folks carry on the legacy because our history is being researched, and it’s being told by others. I want us to tell it. Our history is so rich. I would just hope that someone would pick it up and carry it on and make sure that it is accurate.”

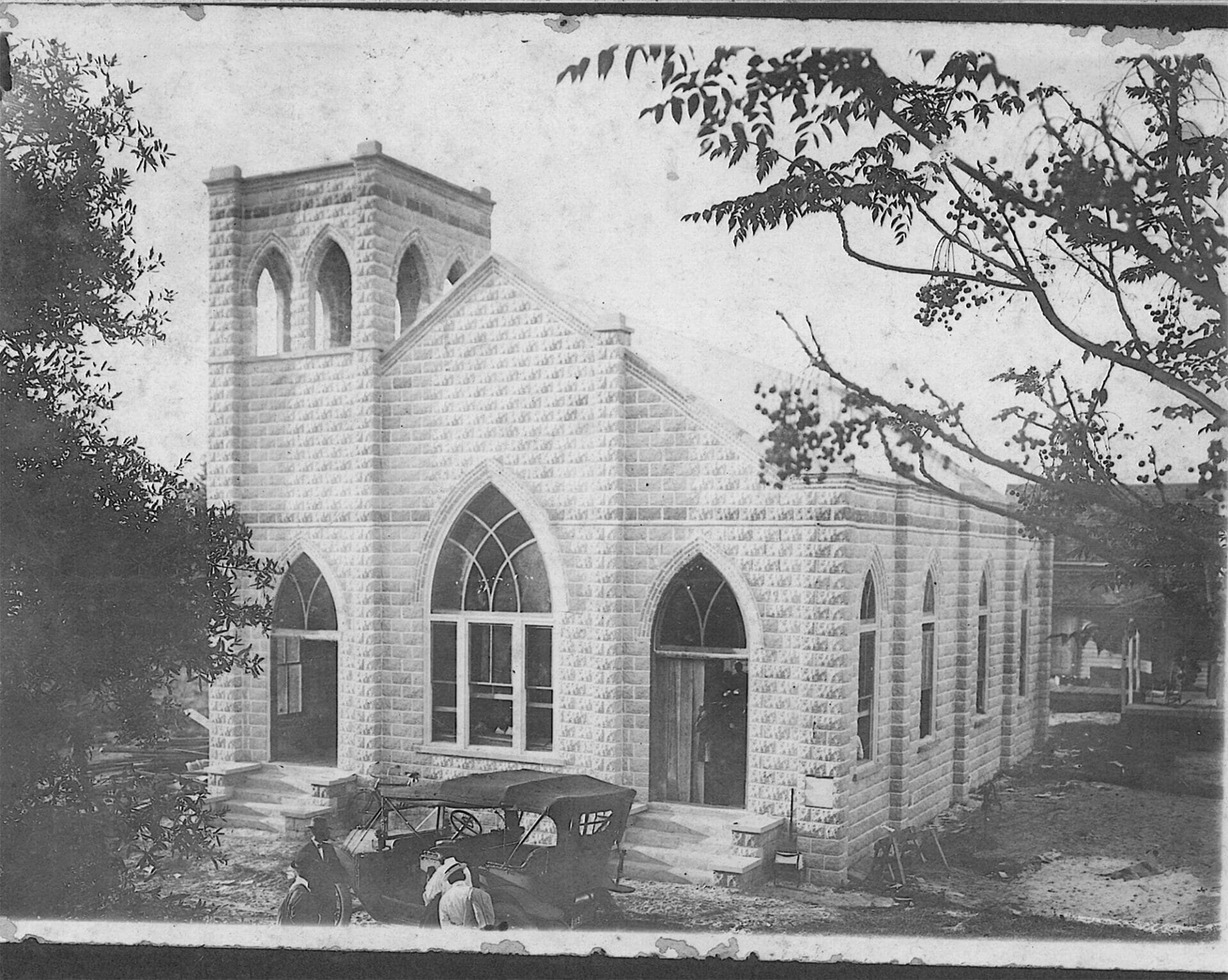

The community built St. John’s Baptist Church, one of the first churches in the Lakeland area.

You can learn more about Moorehead by visiting the Special Collections Room in the Lake Morton Library here in Lakeland, or by visiting the Polk County History Center in Bartow.