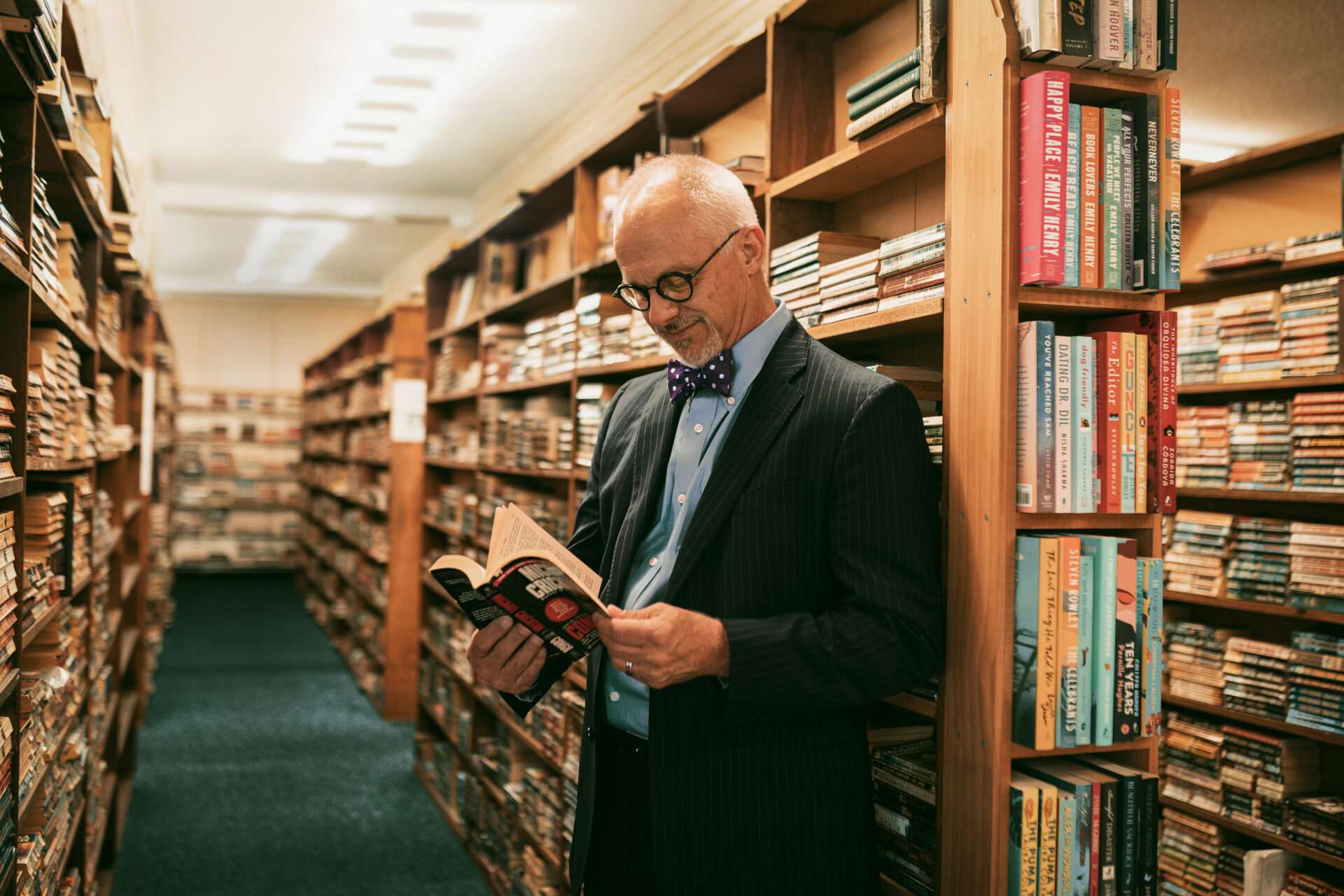

Meet the Presidents

Dr. Randy Avent

President of Florida Polytechnic University

Written By RJ Walters | Photography in Inklings Book Shoppe by Jordan Randall and Jon Sierra

He has one final lap—the curves, the “whoops,” the stiff competition—in him before he truly rides off into the sunset.

When Randy pulls up on his bright orange KTM dirt bike, you’d think he’s just one of the guys when he removes his helmet and starts talking about fixing up his dad’s old truck or a woodworking project he’s finishing.

But if you saw him the next business day the helmet would be replaced with studious glasses, he would probably be donning a suit and sharp purple tie, and if you were fortunate enough to have reserved some time with him in his office, you would be trading wisdom with the first and only president of his kind.

Some will remember the long and sometimes contentious process that preceded the founding of the state’s 12th public university. It was a show of political fireworks involving then Senate budget chairman JD Alexander and his plea to turn Florida Polytechnic—then a branch of the University of South Florida—into a standalone STEM focused institution in rural Polk County.

Florida Polytechnic has quickly, if imperfectly, become an innovative, hands-on learning research university that has partnerships with Mosaic, Lockheed Martin, Cisco and more. It is a career runway for students that the Tampa Bay Business Journal reported produces graduates who have median earnings of $57,900 one year after graduation, 35% higher than the average public school graduate in Florida.

The first class of students at Florida Poly was 554 students during the fall of 2014, and Avent said there were around 30 employees when it launched, including roughly 10 faculty. Today, enrollment is at more than 1,500 undergrad students, and the school website states more than 150 staff and 73 faculty work there.

It’s been a wild ride to get there.

“There were six legislative mandates that had to be met, and when Ava Parker (now the president of Palm Beach State College) walked in as [the first] employee, she had a year and a half, and she had to hire anybody she could,” Avent recalls. ”Ava got the university ready to open just by her sheer power and devotion to the university.”

Avent remembers “100-hour weeks” early on, and it was an unheralded challenge for a brilliant scholar who worked for Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for nearly two decades, at one time served as a chief scientist for the U.S. Department of Defense, and who said he was once happiest with “his door shut, solving technical challenges and writing papers.”

Yet, when he released a public letter on July 24 stating he would be stepping down as President at the end of the 2023-24 school year, it signaled the accomplished 65-year-old father of three realized he has grown exponentially as a leader by taking on this challenge.

When President Avent isn't in the fast lane of growing a university, he can often be found gripping the throttle of a dirt bike.

“I never imagined that I would be able to help establish a brand-new STEM university and mold the way it would serve students, industry and the entire state,” he wrote in a 411-word message sharing his plans to transition to a faculty role.

He and his staff had to prove the credibility of the institution early on, and they led Florida Poly to its regional accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges in 2017 and its critical ABET Accreditation in 2019.

The infrastructure has followed.

The 90,000 square foot state-of-the-art Applied Research Center opened last fall, a third student residence hall is under construction and a new engineering building is in the works to break ground this fall.

Additionally, the Global Citrus Innovation Center opened, the fruit of a momentous public-private partnership with Fortune 500 company International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF). Avent has long held the vision of building a research park for public-private partnerships on open land within miles of the university, but he acknowledges it has progressed slower than he hoped.

“One of the things that keeps me up at night is how many warehouses [that are being built on nearby land] because they are really going to shut the door on that opportunity,” he said.

Avent said the university graduates 300-400 talented students each year, but “they all leave Polk County” because high-tech jobs with competitive wages and growth opportunities are not currently part of the area’s infrastructure.

“Polk County’s not gonna get anything out of this university if we can’t start attracting some high tech economies,” he said. He’s not completely pessimistic, noting the domino effect that hopefully started with the IFF partnership and mentioning the impact he expects to see from SunTrax—a 400-acre site that involves a partnership with Florida Poly and the Florida Department of Transportation that will develop and test emerging technologies that improve and advance transportation.

Avent is proud that he leads a university where they “teach theory, not technology.” He says STEM is not just about buzz categories like 3D printing and robotics, it’s foundationally about understanding hard math like triple integrals on closed contour surfaces and being able to determine whether sequences converge or diverge.

Florida Poly challenges students to not only be great at solving complex problems, but also to be comfortable working on teams and presenting their findings to peers, skills that enable them to be more career ready.

“You know, the old joke, ‘How do you tell an engineer is extroverted?’” Avent quips. “He looks at your shoes when he talks to you.”

“I never imagined that I would help establish a brand-new STEM university and mold the way it would serve students, industry and the entire state.”

To combat some of the stress related to his job, Avent truly did return to one of his pastimes of yesteryear, connecting with a group of Florida Poly students along the way.

He rode dirt bikes all through high school, and then picked the hobby back up when his kids wanted to ride. But ever since, he had only daydreamed about it on occasion.

Then one day, Jacob Livingston, who at the time was student government president, showed off a picture of his new street bike to Avent. Avent advised against it because of how dangerous they are, and Livingston said his grandparents echoed that sentiment so much that they told him they would buy him a car if he sold it.

“I said, ‘Jake, you take them up on that deal, and then go out and buy a dirt bike,’” Avent recalls.

One thing led to another. Livingston did purchase a dirt bike and invited the President out for a spin. Avent rekindled his love for racing at spots like Croom State Park and Bone Valley—often riding with several students—and eventually purchased a couple of KTM bikes to race in hair scrambles and enduros.

For a leader who has helped cast the vision for an institution that has the power to impact generations, it’s something exhilarating that allows him to live in the moment without getting lost in the details.

“On a dirt bike, if you’re not worried about the 10 feet in front of [you], you’re gonna pay for it,” he said.