Written by Adam Justice | Photography by Tina Sargeant

Uniquely American, the drive-in theater has emerged as a testament to our country’s long infatuation with the silver screen. These modern amphitheaters introduced a new generation of movie-goers whose nationalism in the 1930s and ’40s spurred them to seek experiences that were truly American. Drive-ins filled that niche as an authentically American form of entertainment where you could sit in your Oldsmobile, eat hotdogs, and watch the newest cut from Hollywood.

Later, drive-in theaters were effective contributors to the family entertainment boom of the ’50s and early ’60s. They were made popular in part by the rising status of America’s automobile culture and a new lifestyle centered on other such modern conveniences. At its peak, the age of the drive-in included more than 4,000 theaters nationwide.

Later, drive-in theaters were effective contributors to the family entertainment boom of the ’50s and early ’60s. They were made popular in part by the rising status of America’s automobile culture and a new lifestyle centered on other such modern conveniences. At its peak, the age of the drive-in included more than 4,000 theaters nationwide.

With their popularity skyrocketing, drive-ins gradually became less known as family destinations and more as “passion pits,” thanks to the throngs of hormone-laden teenagers who preferred the privacy of an in-car date. This newfound reputation helped to make drive-in theaters the ideal settings for the new American youth movement of the ’60s and ’70s.

Camden, New Jersey, rightfully claims to be the home of the American drive-in theater. It was there that chemical company mogul Richard Hollingshead Jr. opened the first drive-in in 1933 after having been awarded the patent for the concept only weeks earlier. Promoting the venue with the tagline, “The whole family is welcome, regardless of how noisy the children are,” Hollingshead revolutionized the film industry by transforming it from being a mere pastime into a family event.

These outdoor theaters were especially popular in rural areas where Tinseltown seemed worlds away and vast outdoor spaces were plentiful. They quickly turned into pop culture icons themselves, despite which icons they premiered on their screens, and it became fashionable to catch a flick at the local drive-in. But, as time passed and Hollywood grew alongside technology, drive-ins lost footing to larger indoor theaters which became more and more prominent with each subsequent generation.

In recent years, however, pop culture has undergone a retrospective makeover. It is truly the age of eBay and irony, so anything currently

in-style is unabashedly old-fashioned; the words vintage and retro are thrown around to describe anything from luggage to architecture these days. Of course, Hollywood bleeds itself on fashion trends, so it’s no surprise that we’ve recently been invaded by an onslaught of modern remakes of classic films — even remakes of films produced less than a decade ago. Perhaps the slimiest part of modernity’s underbelly is how we’ve allowed Hollywood to cash in on movies that were initially pretty good but are now renovated to look slicker, despite mundane casting.

But, there is that proverbial silver lining to the recycled silver screen. Classic drive-in theaters have found themselves amid a renaissance. (It’s just too bad we failed to realize their worth before 75 percent of them unplugged their projectors for good.) Now, aided by our current reflective interests, hip young families, older nostalgic baby boomers, and a fresh population of teens who are rabid for anything social and nuanced, have offered drive-in theaters a golden opportunity for a much awaited sequel.

Lakeland is fortunate to have one of only eight drive-in theaters still operating throughout Florida. The Silver Moon Drive-in, located at 4100 New Tampa Highway, has been screening movies since April 13, 1948, making it the second oldest drive-in in the state and the first to open in Lakeland.

It was originally owned and operated by Mr. I. Q. Mise and Mr. M. G. Waring, then sold in 1952 to Floyd Theaters, a statewide theater chain. When the company went bust in the early ’90s, its former president, Harold Spears, founded Sun South Theaters and purchased the Silver Moon. Mr. Spears still owns the theater and is proud of its designation as Polk County’s only operational drive-in movie theater. In 1986, Mr. Spears added a second screen to the theater, making it a double-feature venue that can now accommodate approximately 500 cars and opens to an average of 49,000 people a year.

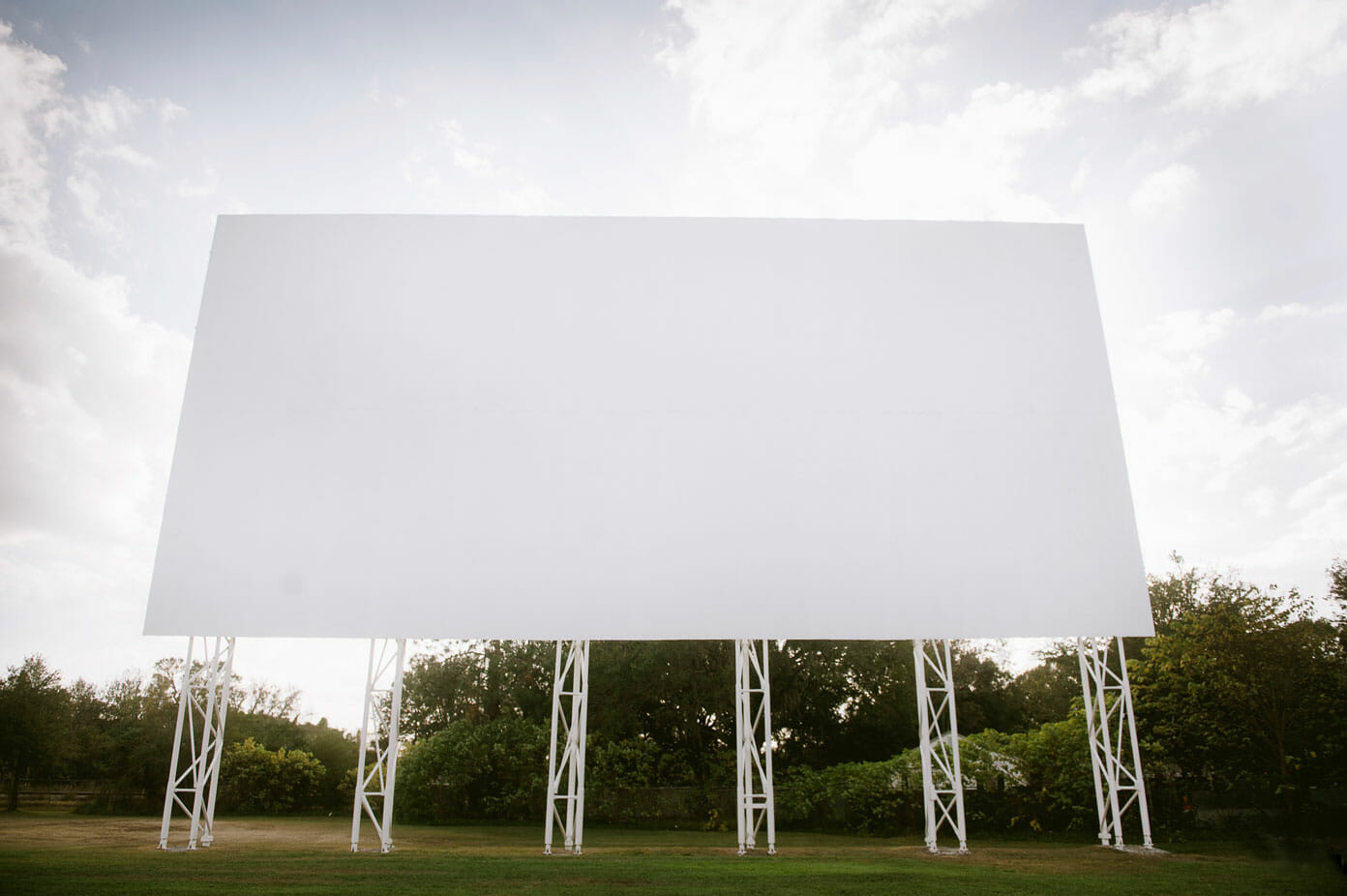

For better insight into the story and identity of the Silver Moon, I met with Charlie Rickman, the theater’s manager, and James Andrews, a supervisor for Sun South Theaters. I arrived at the drive-in midday, and the entire scene seemed something quite surreally Hollywood itself with its deserted parking lot and looming blank screen. Rickman and Andrews were more than happy to give me the grand tour of the place and provide a better sense of the Silver Moon then and now.

Originally, the theater was half its current size and backed by a dense patch of forest. As we stood in the center of the large viewing lot, which was completely vacant except for a number of speaker poles still lining the aisles, Rickman pointed to the base of the large screen and said, “That’s where the snack bar used to be.” Attendants formerly worked as wait staff, moving like ants to and from the base of the screen, jotting down orders from alongside car windows.

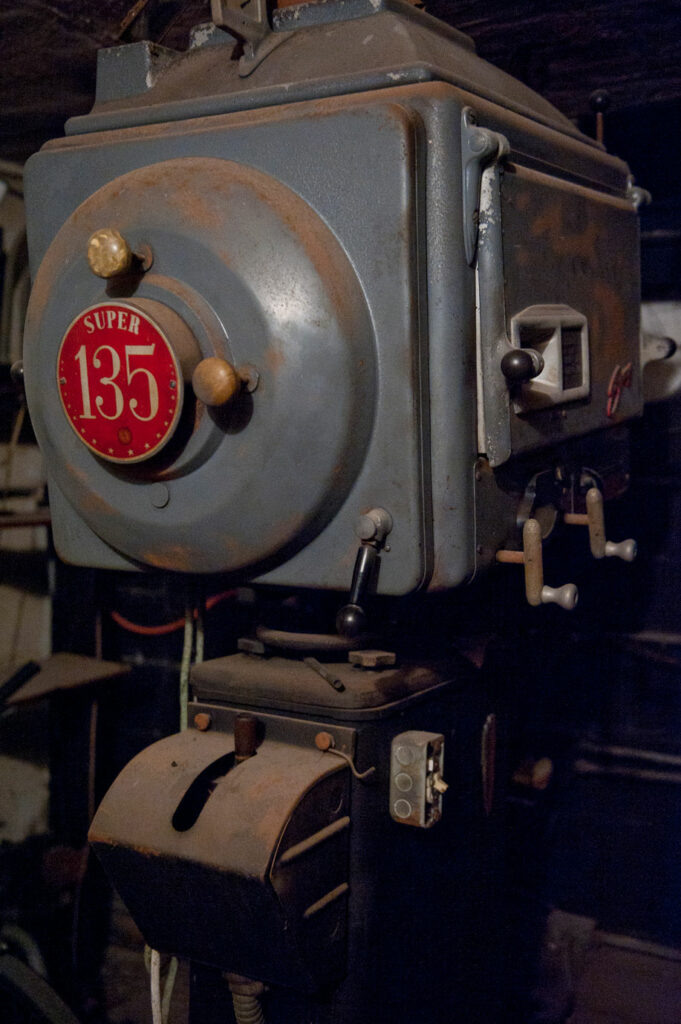

The movies were originally projected from a dugout in the center of the parking lot. Jokingly referred to by Rickman and Andrews as “the dungeon,” this bunker is still accessible and houses one of two large antique projectors used in the theater’s early years. The bulky machine more closely resembles a large locomotive engine and would probably radiate as much heat. As Andrews hit the switch, the dinosaur jerked and fired up, requiring us to yell over its loud generator. The projectionist endured hours of grueling heat and noise each evening in this claustrophobic space.

The original method of screening movies involved a dual-projector system. Since films arrived on two large reels of 35-millimeter film, a theater had to have two projectors. As the movie wound to the end of one reel, small indicators called “burn marks” would appear in the corner of the film. These marks signaled the projectionist to start the other projector in order to seamlessly continue the picture.

In the ’70s, theaters starting using another system that utilized large rotating platters on which both reels of film could be spliced and placed for one continuous feed. This required theaters to need only one projector. Both of these systems are now obsolete with the advent of digital technology. Although there are still theaters operating on a film-based projection system, Rickman and Andrews predict it is only a matter of months before major production companies abandon film altogether.

Last year, the Silver Moon took a giant leap into the 21st century by purchasing two state-of-the-art digital projectors. These computerized behemoths are operated via touchscreen technology and are each equipped with an oversized light bulb comparable to the circumference of a basketball. They run on separate video and audio systems, one for each side of the drive-in, and are effortless to operate. Movies arrive on compact cartridges that resemble 8-track tapes (how retro). They’re loaded into the back of the projector and played at the touch of a screen; perhaps less dramatic than the old 35-millimeter film process but much more efficient. Efficiency comes with a price, however, and not only monetarily.

As Rickman and Andrews described these two cutting-edge projectors, they mentioned an interesting dichotomy: How do you retain a drive-in movie theater’s unique nostalgia while conforming to the technological demands of the 21st century? In an age when technology and trends fade in and out in a matter of months, historic drive-ins find themselves in a curious predicament, having to initiate a massive self-reassessment that affects their new identities as some of the last bastions of true Americana.

As drive-ins have succeeded in retaining their antique appeal, they‘ve also somehow managed to keep their unusually low admission prices. The Silver Moon remains one of the most inexpensive tickets around, charging $4 for people age ten and over, and only $1 for children between the ages of four and nine. These prices have remained constant throughout the modernization process when basic equipment, i.e. projectors, cash registers, audio equipment, and payment methods, have had to be revamped to accommodate the new age. But, as the

drive-in continues to progress digitally and an already much larger overhead continues to grow, will the Silver Moon remain so accessible and cost efficient?

“Without a doubt,” says Rickman. And, it’s difficult not to believe him. Despite the steeply rising costs of being digital, the Silver Moon is dedicated to remaining an affordable attraction for family entertainment. Through shifting tides in technology and culture, the Silver Moon has remained one of Lakeland’s most coveted gems for nearly 80 years. It continues to grow according to rising demands but has successfully retained an important part of its identity. To peer beyond its large welcoming neon sign and see anything other than its legacy as a Lakeland icon would be a modern approach, and we are all too old-fashioned for that.